The tip-and-pour method of transferring chemicals, as well as poorly designed pumps, can expose workers to injury and companies to significant financial losses.

In the manufacturing of plastics, workers often transfer potentially hazardous liquid additives such as plasticizers, colorants, dyes, lubricants, antimicrobials and flame retardants into smaller containers or directly into tanks or machinery. At times, liquid solvents and cleaners used for maintenance may be transferred as well.

Chemicals such as acetone also are used in plastics machining and for 3D printed parts for vapor polishing, which – when applied to the surface of plastic – alters the finish to a high gloss.

These chemicals are toxic, corrosive, reactive, and flammable, emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or are even potentially explosive and the danger of accidental contact, even for short periods, can pose a severe hazard to workers. The transfer of chemicals at the point of use, whether it’s done in plastics manufacturing, fabricating or machining, can have serious consequences when manual “tip-and-pour” techniques or poorly designed pumps are used.

In addition to the potential for injury, there also can be serious financial ramifications for the facility involved. The risks include the cost to treat injuries or perform cleanup, as well as workers’ compensation claims, potential liability, OSHA fines, loss of expensive chemicals and even facility/production shutdown.

“It can be catastrophic to a company if toxic or highly flammable material is accidentally released at the point of use,” says Deborah Grubbe, PE, CEng, and founder of Operations and Safety Solutions, a consulting firm specializing in industrial safety. “Companies have to assume that if something can go wrong during chemical transfer, it will, and take appropriate precautions to prevent what could be significant consequences.”

Spiraling Costs of Loss of Containment

Grubbe, who has 40 years of experience working in the chemical, oil and gas industries, including at DuPont, NASA and for the U.S. military, says, “Any time you lose containment; you have an issue that can spiral out of control.”

Corrosive chemicals, for example, can burn skin or flesh. Some chemicals are toxic when touched or inhaled. Cyanotic agents can be particularly dangerous or even fatal, since they rob the body of oxygen. Many chemicals are flammable, and can be ignited by even the smallest spark from nearby motors or other mechanical equipment.

“There is no such thing as a small fire in my business,” says Grubbe.

In addition to cost of cleanup or treating injuries, there also are indirect costs that can be incurred. These include supervisors’ time to document the incident and respond to any added government inspection or scrutiny, as well as the potential for temporary shutdown of the facility.

“The indirect costs can be as much as two to four times the direct costs,” says Grubbe. “Not to mention potential liability, workers’ compensation issues, regulatory fines or potential actions from OSHA or the EPA.”

Chemical Transfer Techniques

Grubbe notes that traditional practices of transferring liquid chemicals can suffer from a number of drawbacks. Manual techniques, such as the tip-and-pour method, still are common today. Tipping heavy barrels, however, can lead to over pouring or the barrel toppling.

“Some companies choose to transfer of chemicals manually, but it is extremely difficult to control heavy drums,” cautions Grubbe. “I’d recommend against it because of the probability of a spill is so high.”

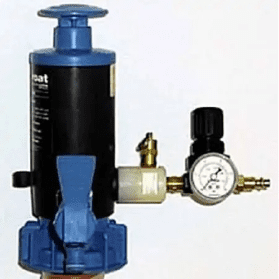

Although a number of pump types exist for chemical transfer (rotary, siphon, lever-action, piston and electric), most are not engineered as a sealed, contained system. In addition, these pumps can have seals that leak or can wear out and can be difficult to operate, making precise volume control and dispensing difficult.

In contrast, sealed pump systems dramatically can improve the safety and efficiency of chemical transfer.

“A sealed, contained system is ideal when dealing with a toxic, flammable, or corrosive liquid,” says Grubbe. “With sealed devices, you can maintain a controlled containment from one vessel to another.”

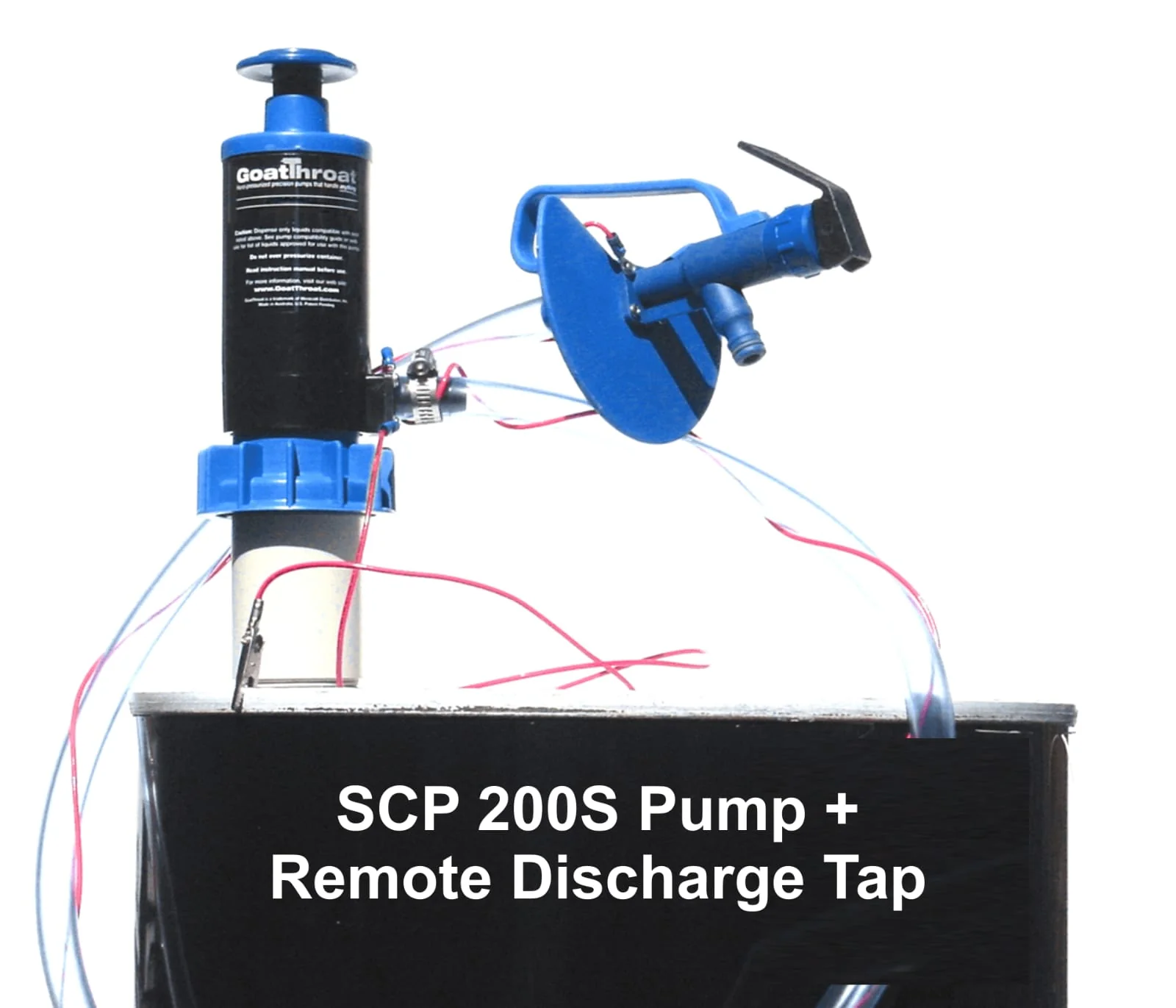

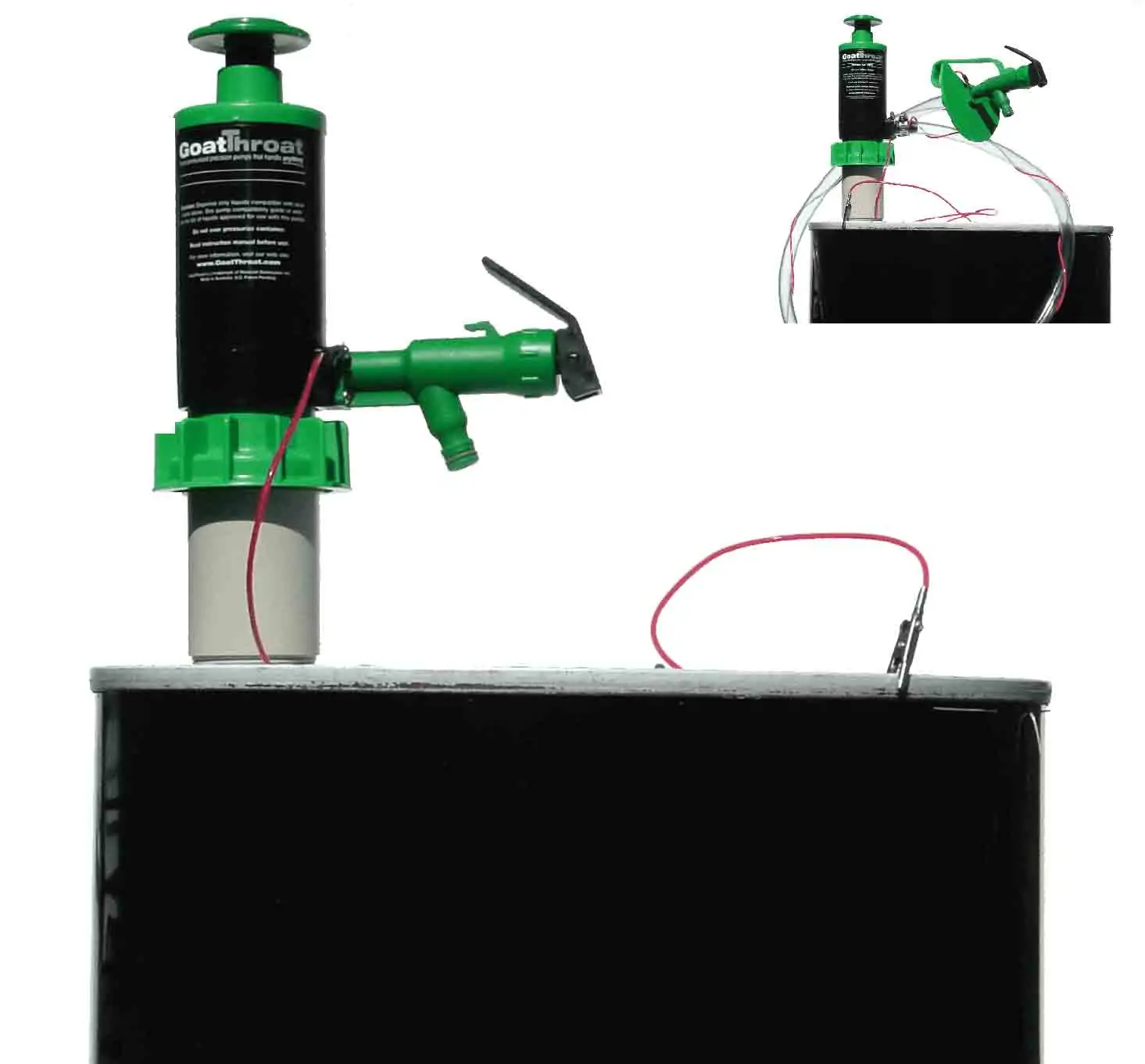

Small, versatile, hand-operated pressure pumps are engineered to work as a sealed system. The pumps can be used for the safe transfer of over 1,400 industrial chemicals, including the most aggressive acids, caustics and solvents.

These pumps function essentially like a beer tap. The operator attaches the pump, presses the plunger several times to build up a low amount of internal pressure and then dispenses the liquid. The tap is configured to provide precise control over the fluid delivery, from slow (1ML/ 1 oz.) up to 4.5 gallons per minute, depending on viscosity.

Because such pumps use very low pressure (<6 PSI) to transfer fluids through the line and contain automatic pressure relief valves, they are safe to use with virtually any container from 2-gallon jugs to 55-gallon drums.

Adoption of Sealed Pump Systems

East Coast Precision Manufacturing is a precision plastic part fabricator that machines many types of plastics such as acetal, abs, acrylic, nylon, PVC, PTFE, phenolics and polycarbonate.

To improve the safety and efficiency of one of its processes, the Chester, Conn.-based company sought to upgrade from a manual tip-and-pour method of transferring chemicals from a 5-gallon drum into a designated vessel.

“We wanted to avoid the potential strain or spillage of pouring from a 5-gallon drum,” says Chris Marchand, an East Coast Precision Manufacturing engineer. “We needed a pump that was able to safely contain and resist aggressive chemicals.”

As part of his online research, Marchand decided to utilize a sealed chemical pump system.

“Because the pump system is sealed and uses low pressure to transfer chemicals, it prevents overpouring, spills and leaks and keeps any potential VOCs contained,” says Marchand. “We have found that it minimizes clean up and eliminates wasted inventory and content evaporation.”

Marchand appreciates that an available version of the pump is safe to use around flammables because it is static-conductive while another version is explosion-proof, though those capabilities are not required for his process.

He notes that the sealed pump system is easy to use, since operators only need to pump the plunger a few times and then open a tap.

“It is a much safer, more controlled approach than trying to lift and pour chemicals from a heavy 5-gallon drum,” concludes Marchand. “We expect to get many years of use from our labor-efficient, flow engineered system.”