Manufacturing Industry Case Studies

Cosmetics Manufacturer Improves Processes Thanks to GoatThroat Pumps

For the passed fifteen years, Florida-based Earth Supplied Products has its hand in the beauty formulas of a wide variety of cosmetics giants like Estee Lauder, Avon and Revlon just to name a few. Catering primarily to companies based on the East Coast, Earth Supplied Products specializes in providing natural, hand-mixed cosmetic additives and ingredients to the personal care and cosmetic industries. Earth Supplied Products uses oils from natural sources like Black Walnuts, Brazil Nuts, Cotton Seeds, Pecans and even Pumpkins.

These oils, purchased in 55-gallon drums, are normally dispensed from a traditional spigot style tap. The problem for company owner Peter Boncelet was the process of tapping them, which required each cumbersome 500-pound, 55-gallon drum to first be tipped onto its side. The act of tipping the large heavy cylinders was complicated and potentially dangerous. In addition, having the drums lying down on their sides took up a considerable amount of space.

Wanting to improve worker safety, Boncelet conducted an Internet search that lead to his discovery of GoatThroat™ Pumps. He purchased one. Living up to its claim, the pump worked perfectly when inserted atop the upright drum. In addition to eliminating the tipping problem, the pump performed excellently at volumes up to four gallons per minute, with oils of all types and weights. Because it pressurized the drums, the pump made drawing fluid and emptying drums much easier than with the gravity-fed spigot. Providing improved volume control and increased accuracy, the pump eliminated waste and reduced costs. “The pumps have turned out to be a safe and smart solution for us”, says Boncelet.

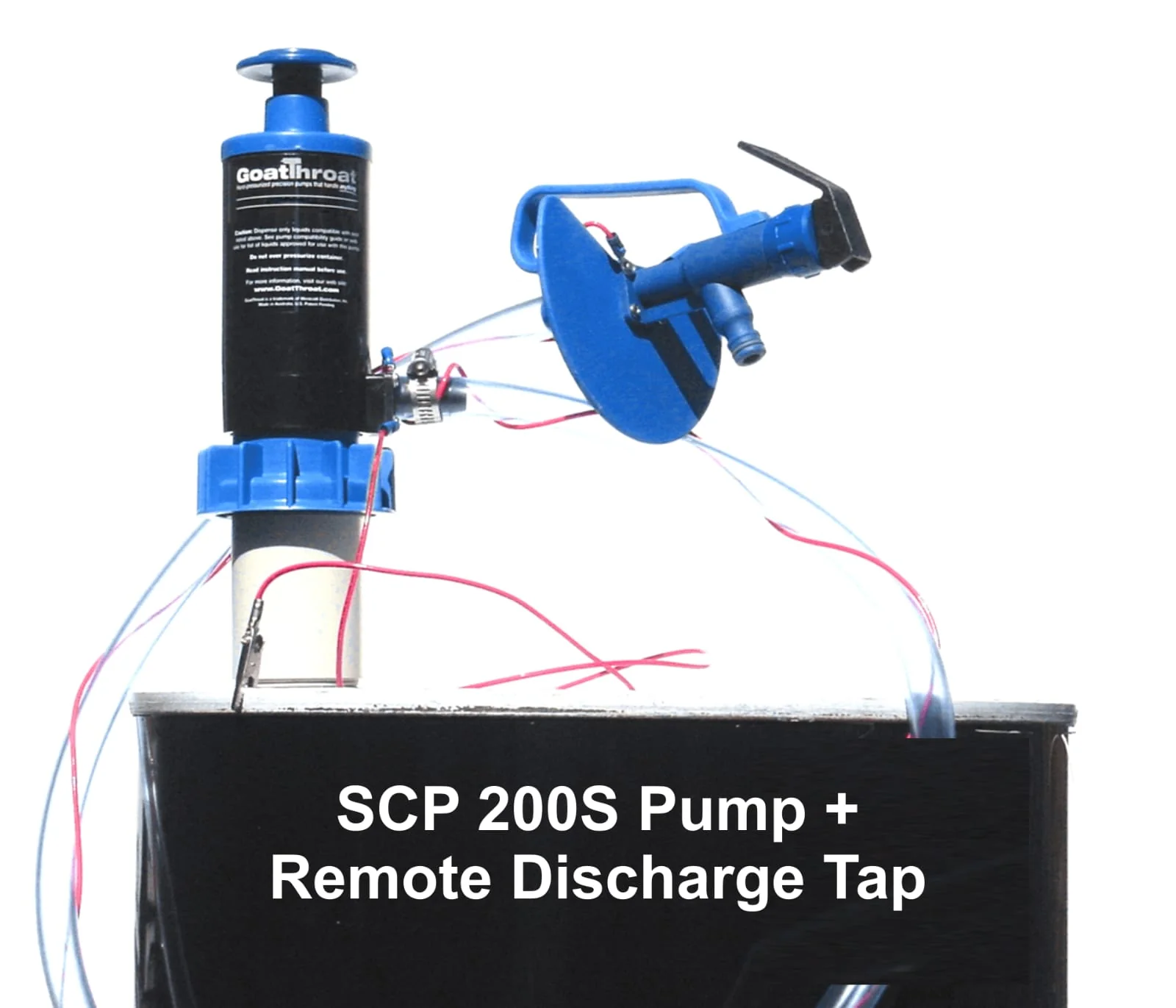

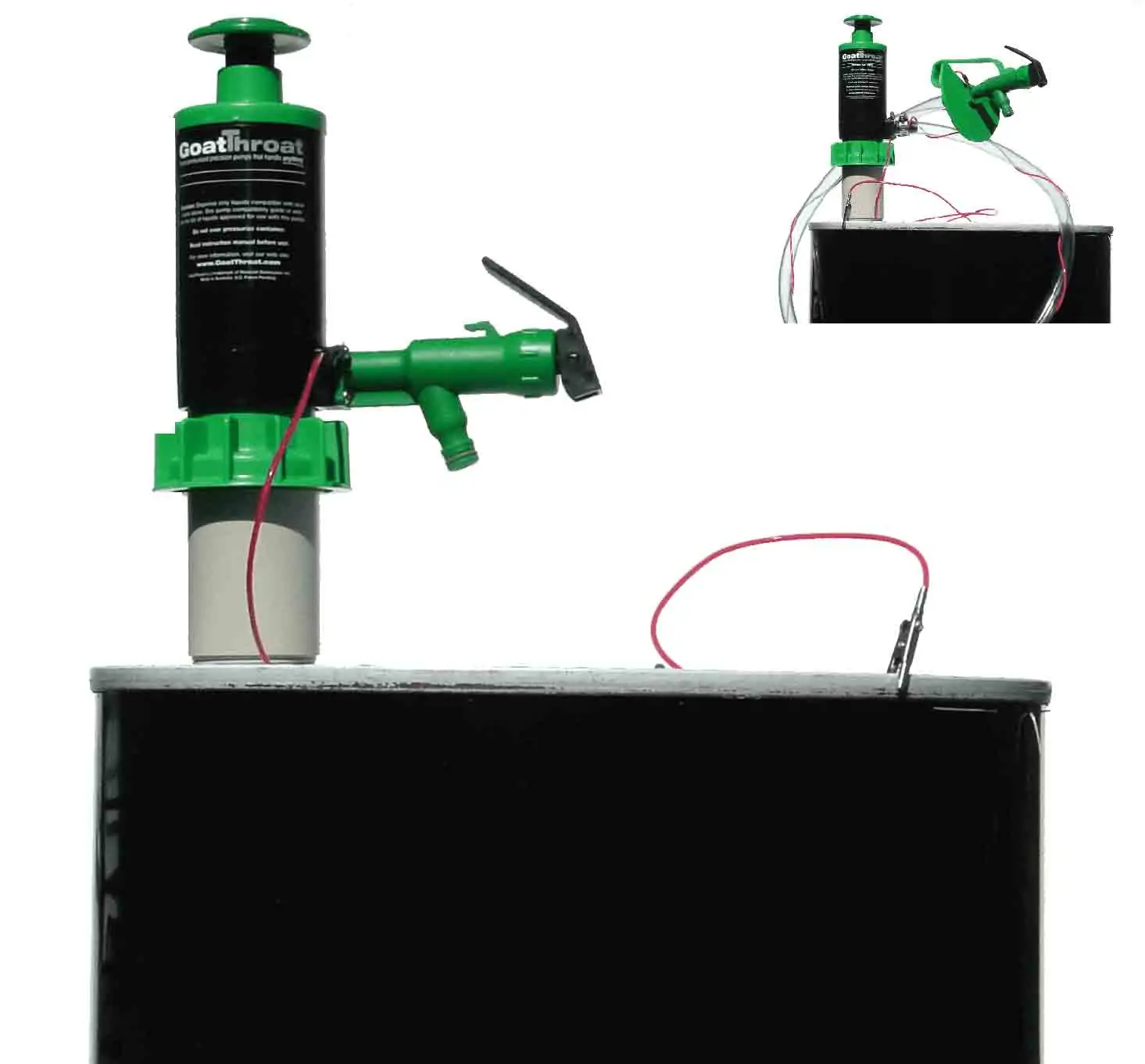

“Not only are they more convenient, they are really cost effective. They have a life expectancy of 10 to 15 years. They eliminate the potential safety risk. And they can be easily cleaned, sanitized and re-used.” GoatThroat™ Pumps are made of chemical grade polypropylene, and all components meet U.S. FDA requirements under CFR Title 21, sections 170-199. The pumps can be used to dispense over 700 different fluids in any industry application that requires easy, safe and cost effective fluid transfer/decanting. With a unique range of adapters for just about any opening, GoattThroat™ Pumps can pressurize any container from 5 to 55-gallons in seconds. And with an optional remote tap system, a pump can easily deliver fluids up to a distance of ten feet from the drum.

SAFETY AT POINT OF USE

Every day industrial workers transfer potentially hazardous chemicals, such as solvents, acetones, lubricants, cleansers, and acids, from large drums into smaller containers, or machinery. This transfer of chemicals at the point of use, however, can have serious consequences when manual “tip-and-pour” techniques or poorly designed pumps are used.Whether the chemicals are toxic, corrosive, reactive, flammable, emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or are even potentially explosive, the danger of accidental contact, even for short periods, can pose a severe hazard to workers.In addition to the potential for injury, there can also be serious financial ramifications for the facility involved.

The risks include cost to treat injuries or perform cleanup, as well as workers’compensation claims, potential liability, OSHA fines, loss of expensive chemicals and even facility/production shutdown.“It can be catastrophic to a company if toxic or highly flammable material is accidentally released at the point of use,” says Deborah Grubbe, PE, C.Eng, and founder of Operations and Safety Solutions, a consulting firm specializing in industrial safety. “Companies have to assume that if something can go wrong during chemical transfer; it will, and take appropriate precautions to prevent what could be significant consequences.”

Spiraling Costs of Loss of Containment

Ms. Grubbe, who has 40 years of experience working in the chemical, oil and gas industries,including at DuPont, NASA, and for the U.S. military, says “Any time you lose containment; you have an issue that can spiral out of control.”Corrosive chemicals, for example, can burn skin or flesh. Some chemicals are toxic when inhaled. Cyanotic agents, for instance, can be particularly dangerous or even fatal,since they rob the body of oxygen.Many chemicals are flammable as well and can be ignited by even the smallest spark from nearby motors or other mechanical equipment. “There is no such thing as a small fire in my business,” says Ms. Grubbe.

In addition to cost of cleanup or treating injuries, there are also indirect costs that can be incurred. These include supervisors’ time to document the incident and respond to any added government inspection or scrutiny, as well as the potential for temporary shutdown of the facility.“The indirect costs can be as much as 2-4 times the direct costs,” says Ms. Grubbe. “Not to mention potential liability, workers’ compensation issues, regulatory fines or potential actions from OSHA or the EPA.”

Chemical Transfer Techniques

Traditional practices of transferring liquid chemicals suffer from a number of drawbacks. Manual techniques, such as the tip-and-pour method, are still common today. Tipping heavy barrels, however, can lead to over-pouring or the barrel toppling.“Some companies choose to transfer of chemicals manually, but it is extremely difficult to control heavy drums,” cautions Ms. Grubbe. “I’d recommend against it because of the probability of a spill is so high.”Although a number of pump types exist for chemical transfer (rotary, siphon, lever-action,piston and electric), most are not engineered as a sealed, contained system. In addition, these pumps can have seals that leak, are known to wear out quickly, and can be difficult to operate,making precise volume control and dispensing difficult.In contrast, sealed pump systems can dramatically improve the safety and efficiency of chemical transfer.

“A sealed, contained system is ideal when dealing with a toxic, flammable, or corrosive liquid,”says Grubbe. “With sealed devices, like GoatThroat pumps, you can maintain a controlled containment from one vessel to another.” Small, versatile, hand-operated pressure pumps are engineered to work as a sealed system. The pumps can be used for the safe transfer of over 1400 industrial chemicals, including the most aggressive acids, caustics and solvents. These sealed-system pumps function essentially like a beer tap. The operator attaches the pump, presses the plunger several times to build up a low amount of internal pressure, and then dispenses the liquid.

The Sealed System Pump tap is configured to provide precise control over the fluid delivery, from slow (1ML/ 1 oz.) up to 4.5 gallons per minute, depending on viscosity.Because such pumps use very low pressure (<6 PSI) to transfer fluids through the line and contain automatic pressure relief valves, they are safe to use with virtually any container from 2-gallon jugs to 55-gallon drums.

Adoption of Sealed Pump Systems

Although Design Mark Industries keeps its chemicals in a vented, explosion-proof room, the supplier of membrane switches, keypads, and touchscreens sought to further improve the safety and efficiency of transferring acetone and acetate-based chemicals from 55-gallon drums into quart and 5-gallon containers. The chemicals are used in the screen printing process of printed circuitry and graphic overlays.Production Supervisor Vincent Francisco ruled out manual pouring because of the potential of injury and lack of control in dispensing. Instead, he utilized a variety of traditional pumps including rotary, siphon, and lever-action, but found them all unsatisfactory.

“I was replacing the pumps once or twice a year because they kept breaking down, delivered imprecise amounts, and were not designed as completely self-contained, sealed systems,” says Mr. Francisco. After considerable research online, Mr. Francisco decided to utilize a sealed chemical pump system. He considers them a “best practice” technique because the barrel remains upright during the entire transfer process and there is no exposure to VOC vapours.

According to Mr. Francisco, the sealed pump system is intuitive to use because it operates like a beer tap. “Just pump the plunger a few times, open the spigot and dispense. You have full control over how much is dispensed – even the tiniest amounts – or you can leave it open for a continuous flow. It delivers the precise amount needed.”Mr. Francisco adds that the pumps are built for longevity.

Over the past 11 years, he estimates that his company has saved thousands of dollars by eliminating the cost of replacement pumps. “I’ve only replaced one of our three pumps over that time due to constant use, and we could have used it longer,” says Mr. Francisco.Allergy Laboratories Inc., a FDA licensed pharmaceutical manufacturer of biological extracts for the diagnostic testing and therapeutic treatment of allergies, also uses a sealed pump system to transfer acetone from 55 gallon drums to 1 gallon containers for a variety of processes.

According to Charles Cheek, facility manager for Allergy Laboratories, the pharmaceutical chemical delivery process must be very clean and no foreign material can be introduced into the acetone.Because acetone is highly flammable, he was concerned about using an electric pump that could potentially create a spark. As a result, he decided to purchase a pump that had no electrical or moving parts that could create a hazard.The company found sealed-system pumps to be a much safer way to transport chemical liquids.

“There is no spillage, splatter, overpouring, leaking, or VOCs because the system is self-contained. There is no sprayback and we do not get chemicals on our hands. It is a nice, clean delivery system” stated Mr. Cheek. Besides enhancing safety, Mr. Cheek says a sealed system can prevent loss of expensive chemicals like acetone. “I haven’t lost any product due to the pumps. They eliminate evaporation, do not leak or drip and I can adjust the flow to get the exact amount I need without spilling or overflow.” Mr. Cheek says he also utilizes a sealed-system pump to transfer comprehensive boiler water treatment solution to mitigate scale and corrosion of the boiler system. Previously, he had to fill a glass beaker with the chemical, climb a ladder and pour the chemicals into the top of the tank. Now, that work is performed with the help of the pump and 6’ extension hose accessory to efficiently deliver the cleaning chemicals.“Every time inspectors come in, they say we have the cleanest boiler they have seen,” says Mr.Cheek. “With this chemical transfer system, I’m able to transfer exactly what I need to get the job done.”

GoatThroat Allows Company to Comply with Open Use Restrictions

When a North Carolina biopharmaceutical company’s productivity was limited by the state fire code’s “Open Use” restrictions, the company’s Environmental Safety Department found itself facing chemical storage challenges at a new level. Engaged in the design, discovery and development of NNR Therapeuticas, a new class of drugs for the treatment of multiple diseases and disorders of the central nervous system, the biopharmaceutical company used chemicals and solvents such as ether, methylene chloride, chloroform, hexane, ethyl acetate, isopropyl alcohol, methanol and toluene in its process. The company’s productivity problem stemmed from fire codes specifying that five-gallon containers of these types of fluids had to be stored on the first floor of their facility, when actually the solvents were needed in the lab on the fourth floor.

Safety is Compromised

The complicated logistics were dictated by restrictions in the fire codes, which limit the storage and use of certain chemicals in multi-level buildings, in order to minimize the potential fire hazards. The codes stipulate that the higher up in the building, the fewer “open-use” containers are allowed, as fumes (VOCs) from high vapor pressure and flammable liquids are fire hazards due to their increased potential for static ignition. In addition, “open-use” allowed excessive VOCs that posed a safety threat.

In order to have the fluids handy on the fourth floor for the lab technicians’ immediate use, the company was facing the possibility of using one-gallon bottles of each of the fluids instead of the more cost-effective five-gallon containers. North Carolina’s fire codes define an “open-system” or “open-use” situation as: “The use of a solid or liquid hazardous material involving a vessel or system that is continuously open to the atmosphere during normal operations, and where vapors are liberated or the product is exposed to the atmosphere during normal operations.”

Also, the code defines non-compliant, open situations as “…situations where hazardous solids or liquids are being dispensed from or into open beakers or containers,” making the process at this North Carolina company a prime example. Based on the facility’s layout, the codes dictate that only containers up to one gallon in size are allowed to be open or stored above the first floor. The situation presented a tough choice for the facility: Continue the time-consuming practice of dispensing chemicals from large containers into smaller ones, and then transporting containers of fluids from the ground floor to the fourth floor; or take on the increased cost of purchasing solvents in smaller-quantity containers so that they could be stored near their point of use in the fourth-floor lab. But, according to the Environmental Safety Department, the answer to the challenge was to eliminate the open-use situation, which would then allow the fluids to be housed on the fourth floor within larger containers. With the new transfer method, it was now possible to meet North Carolina’s closed-used safety codes for dispensing liquids from five-gallon containers on the fourth floor.

However, the metal pumps the company had already tried on the ground floor were not the solution. Every pump they had tested perpetuated the open-use situation, allowing VOCs to escape into the air. Additionally, each one leaked, effectively spewing chemicals onto lab personnel. To make matters worse, because the pumps lacked a stop-flow mechanism, it was easy to overflow the receiving containers, which created a spill hazard. Regardless of the type, none of pumps could comply with the directive of a closed-use situation. Convinced that there had to be a better way, one of the management’s staff members searched online for a solution, finding GoatThroat pumps.

Designed to keep vessels closed, dangerous vapors are sealed within the container during normal operations, except when dispensing fluids, thus satisfying the state’s closed-use requirement. The department also was surprised to find that the pumps could be outfitted for compatibility with more than 700 chemicals, including methylene chloride, which in past tests had quickly compromised the effectiveness of other pumps they had tried.

With fittings compatible with the Rieke Flex Spouts already located the five-gallon chemical containers, it is now possible for research technicians to safely dispense liquids without having to tip the vessels. Depending on the solvent’s viscosity, pumps deliver a steady stream of fluid up to 4 gpm at a low pressure of 4 to 6 psi. A drip-proof faucet has a spring-actuated on-off valve, allowing solvents to be dispensed with control from the safety cabinet into small beakers ready for use, thereby eliminating spills and leaking. Conclusion The new pumps have solved the company’s open-use situation.

Now, except for the 55-gallon drum of toluene, which is also dispensed using one of the pressure pumps, all of the necessary solvent containers can be housed on the fourth floor near the lab technicians. Not only did the pumps solve the logistical situation, they saved the employees time and the company money. Paying for themselves in less than two months, the pumps also provided cost-savings realized when the company was able to purchase solvents in large-quantity containers. After two years, the original pumps are still in use. Dangerous VOCs and odors are greatly reduced, and workers are protected and breathing safely, effectively impressing the Fire Marshall at last inspection.

AT A GLANCE

The company’s productivity problem stemmed from fire codes specifying that five-gallon containers of these types of fluids had to be stored on the first floor of their facility “Open-use” allowed excessive VOCs that posed a safety threat. The answer to the challenge was to eliminate the open-use situation, which would then allow the fluids to be housed on the fourth floor within larger containers. Every pump they had tested perpetuated the open-use situation, allowing VOCs to escape into the air

PUTTING SOLVENTS IN THEIR PLACE

Manufacturer Makes Huge Improvements to Chemical Storage Practices Thanks to GoatThroat

Old ways of doing business are acceptable today if they comply with regulations and get the job done efficiently. A Florida-based manufacturer was unable to meet both of those goals in its production process for precision wire and ultra-fine wire used in microelectronic and semiconductor applications.”This company’s initial challenge was to protect the workers and limit the downside risks of damages, hefty fines and litigation fees, and public relations disasters — and save money,” said Nancy Westcott of Westcott Distribution Inc.

The production process uses numerous solvents and coatings that must be transferred from 55-gallon drums to transfer containers. Workers tapped and tipped the drums and then dispensed the chemicals from leaky spigots into open transfer containers,with additional handling required to transfer the fluids to their point of use. The gravity-fed process involved threading a brass fixture into the small bung in the top of the drum, threading a vent into the large bung, placing the drum on a roll-down drum fixture, and tipping the drum into the horizontal position to dispense the chemicals.

Once the drums were tapped, workers still had to deal with the inherent difficulties that gravity-fed spigot systems presented:

Extracting fluid was labor intensive and awkward.

Spigots clogged easily and were difficult to remove.

It was difficult to control the flow rate, and the spigots leaked, contributing to spills and fugitive inventory loss.

The spigot system did not allow complete removal of all fluid from the drum, so additional labor and handling were required for Resource Conservation and Recovery Act compliance.

Frequently, the workers just left 2 – 5 gallons in the drums. Some of the coatings cost $75 per gallon, resulting in a significant waste of inventory and money. According to the facility manager, “A chemical disaster was always just slip-of-hand away. Moving a 500-pound drum into a horizontal position was complicated for employees and took up a lot of space in the chemical room. There was always a chance that a mistake could hurt the staff or, if the spigot came off during the laying down process, there would be a huge spill. Our staff also had to contend with dripping valves of solvents and the VOCs in the chemical room. ”

A few close calls prompted a production staff member to seek out a new fluid-handling solution. Taking cues from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s information on Process Hazard Analysis, he found a systematic way to identify and analyze the significance of potential hazards associated with the processing or handling of highly hazardous chemicals. Working with his safety manager, the staff member reviewed the shop’s equipment and the manufacturing processes and found that both needed improvement. He located a pressure action pump from GoatThroat Pumps that seemed to meet all of the goals – including efficiency.

“We understand the challenges that dispensing and mixing chemicals present to worker safety and environmental compliance, and we spend a lot of time in our pump lab working on how we can help our customers address them,” said Westcott. In the wire manufacturing facility, the pressure action pumps work by adding less than 6 pounds per square inch of pressure to the vessel to push fluid out of the drum. A spring-activated control on the tap allows precise control of the amount of fluid being dispensed, a rate of 4 gallons per minute, depending on viscosity. There is no need for tipping the drums.

According to the plant manager, “these pumps helped us improve our overall efficiency. By dispensing our chemicals from vertical drums, it has helped us clean up our dispensing area by eliminating drips and leaks. Another advantage is the ability to pump most of our drums almost completely empty. This alone saves us several thousands of dollars per month in disposal costs and chemical purchases. The company has been safely and more efficiently pumping chemicals without incident since 2004.