Open Use Storage in a Laboratory Testing Setting

GoatThroat Pumps Allow Biopharmaceutical Company to Comply with Open Use Restrictions

When a North Carolina biopharmaceutical company’s productivity was limited by the state fire code’s “Open Use” restrictions, the company’s Environmental Safety Department found itself facing chemical storage challenges at a new level. Engaged in the design, discovery and development of NNR Therapeuticas, a new class of drugs for the treatment of multiple diseases and disorders of the central nervous system, the biopharmaceutical company used chemicals and solvents such as ether, methylene chloride, chloroform, hexane, ethyl acetate, isopropyl alcohol, methanol and toluene in its process. The company’s productivity problem stemmed from fire codes specifying that five-gallon containers of these types of fluids had to be stored on the first floor of their facility, when actually the solvents were needed in the lab on the fourth floor.

Safety is Compromised

The complicated logistics were dictated by restrictions in the fire codes, which limit the storage and use of certain chemicals in multi-level buildings, in order to minimize the potential fire hazards. The codes stipulate that the higher up in the building, the fewer “open-use” containers are allowed, as fumes (VOCs) from high vapor pressure and flammable liquids are fire hazards due to their increased potential for static ignition. In addition, “open-use” allowed excessive VOCs that posed a safety threat.

In order to have the fluids handy on the fourth floor for the lab technicians’ immediate use, the company was facing the possibility of using one-gallon bottles of each of the fluids instead of the more cost-effective five-gallon containers. North Carolina’s fire codes define an “open-system” or “open-use” situation as: “The use of a solid or liquid hazardous material involving a vessel or system that is continuously open to the atmosphere during normal operations, and where vapors are liberated or the product is exposed to the atmosphere during normal operations.” Also, the code defines non-compliant, open situations as “…situations where hazardous solids or liquids are being dispensed from or into open beakers or containers,” making the process at this North Carolina company a prime example.

Based on the facility’s layout, the codes dictate that only containers up to one gallon in size are allowed to be open or stored above the first floor. The situation presented a tough choice for the facility: Continue the time-consuming practice of dispensing chemicals from large containers into smaller ones, and then transporting containers of fluids from the ground floor to the fourth floor; or take on the increased cost of purchasing solvents in smaller-quantity containers so that they could be stored near their point of use in the fourth-floor lab. But, according to the Environmental Safety Department, the answer to the challenge was to eliminate the open-use situation, which would then allow the fluids to be housed on the fourth floor within larger containers.

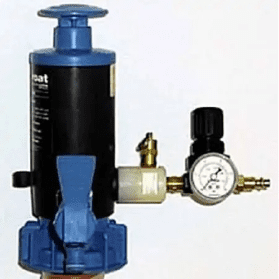

An Open and Closed Case Figure 1

With the new transfer method, it was now possible to meet North Carolina’s closed-used safety codes for dispensing liquids from five-gallon containers on the fourth floor.

However, the metal pumps the company had already tried on the ground floor were not the solution. Every pump they had tested perpetuated the open-use situation, allowing VOCs to escape into the air. Additionally, each one leaked, effectively spewing chemicals onto lab personnel. To make matters worse, because the pumps lacked a stop-flow mechanism, it was easy to overflow the receiving containers, which created a spill hazard. Regardless of the type, none of pumps could comply with the directive of a closed-use situation. Convinced that there had to be a better way, one of the management’s staff members searched online for a solution, finding GoatThroat pumps.

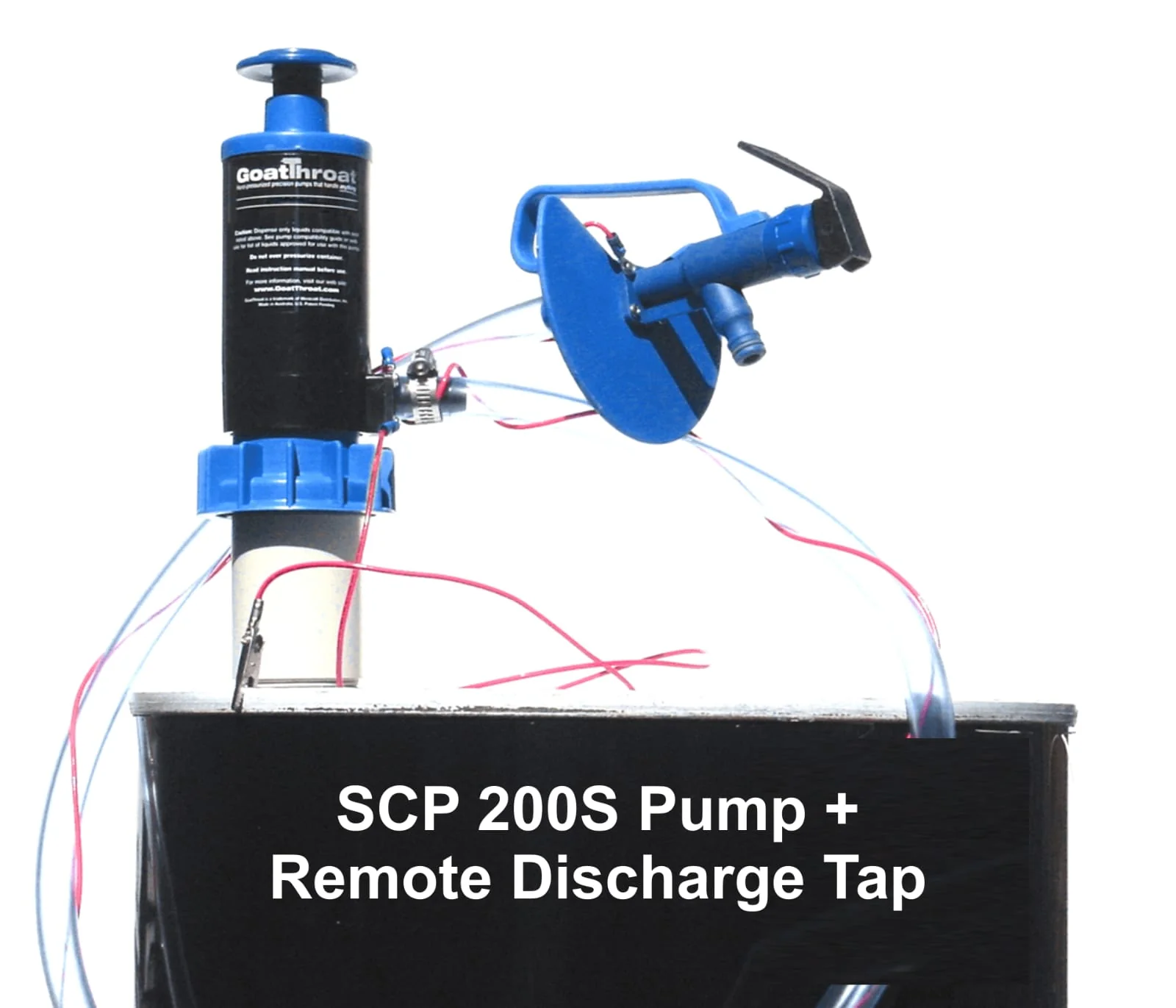

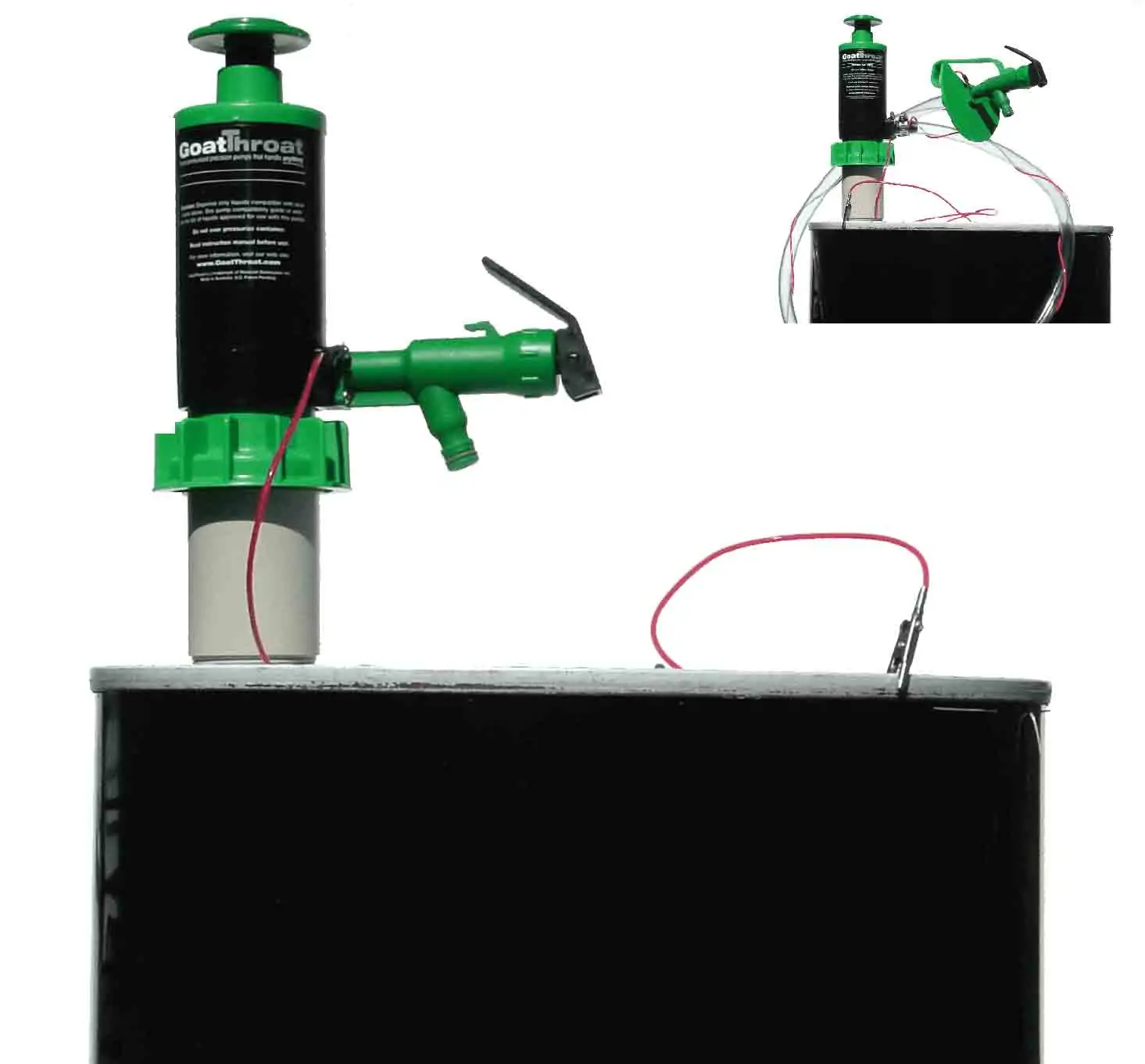

Designed to keep vessels closed, dangerous vapors are sealed within the container during normal operations, except when dispensing fluids, thus satisfying the state’s closed-use requirement. The department also was surprised to find that the pumps could be outfitted for compatibility with more than 700 chemicals, including methylene chloride, which in past tests had quickly compromised the effectiveness of other pumps they had tried. With fittings compatible with the Rieke Flex Spouts already located the five-gallon chemical containers, it is now possible for research technicians to safely dispense liquids without having to tip the vessels. Depending on the solvent’s viscosity, pumps deliver a steady stream of fluid up to 4 gpm at a low pressure of 4 to 6 psi. A drip-proof faucet has a spring-actuated on-off valve, allowing solvents to be dispensed with control from the safety cabinet into small beakers ready for use, thereby eliminating spills and leaking.

Conclusion

The new pumps have solved the company’s open-use situation. Now, except for the 55-gallon drum of toluene, which is also dispensed using one of the pressure pumps, all of the necessary solvent containers can be housed on the fourth floor near the lab technicians. Not only did the pumps solve the logistical situation, they saved the employees time and the company money. Paying for themselves in less than two months, the pumps also provided cost-savings realized when the company was able to purchase solvents in large-quantity containers. After two years, the original pumps are still in use. Dangerous VOCs and odors are greatly reduced, and workers are protected and breathing safely, effectively impressing the Fire Marshall at last inspection.

For more information, contact Nancy Westcott at nwestcott@goatthroat.com or by phone at 646-486-3636.

AT A GLANCE

The company’s productivity problem stemmed from fire codes specifying that five-gallon containers of these types of fluids had to be stored on the first floor of their facility “Open-use” allowed excessive VOCs that posed a safety threat. The answer to the challenge was to eliminate the open-use situation, which would then allow the fluids to be housed on the fourth floor within larger containers. Every pump they had tested perpetuated the open-use situation, allowing VOCs to escape into the air

Putting Solvents in their Place

Manufacturer Makes Huge Improvements to Chemical Storage Practices Thanks to GoatThroat

Old ways of doing business are acceptable today if they comply with regulations and get the job done efficiently. A Florida-based manufacturer was unable to meet both of those goals in its production process for precision wire and ultra-fine wire used in microelectronic and semiconductor applications. “This company’s initial challenge was to protect the workers and limit the downside risks of damages, hefty fines and litigation fees, and public relations disasters – and save money,” said Nancy Westcott of Westcott Distribution Inc. The production process uses numerous solvents and coatings that must be transferred from 55-gallon drums to transfer containers.

Workers tapped and tipped the drums and then dispensed the chemicals from leaky spigots into open transfer containers, with additional handling required to transfer the fluids to their point of use. The gravity-fed process involved threading a brass fixture into the small bung in the top of the drum, threading a vent into the large bung, placing the drum on a roll-down drum fixture, and tipping the drum into the horizontal position to dispense the chemicals. Once the drums were tapped, workers still had to deal with the inherent difficulties that gravity-fed spigot systems presented:

Extracting fluid was labor intensive and awkward. Spigots clogged easily and were difficult to remove.

It was difficult to control the flow rate, and the spigots leaked, contributing to spills and fugitive inventory loss.

The spigot system did not allow complete removal of all fluid from the drum, so additional labor and handling were required for Resource Conservation and Recovery Act compliance.

Frequently, the workers just left 2 – 5 gallons in the drums. Some of the coatings cost $75 per gallon, resulting in a significant waste of inventory and money. According to the facility manager, “A chemical disaster was always just a slip-of-hand away. Moving a 500-pound drum into a horizontal position was complicated for employees and took up a lot of space in the chemical room. There was always a chance that a mistake could hurt the staff or, if the spigot came off during the laying down process, there would be a huge spill. Our staff also had to contend with dripping valves of solvents and the VOCs in the chemical room. ”

A few close calls prompted a production staff member to seek out a new fluid-handling solution. Taking cues from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s information on Process Hazard Analysis, he found a systematic way to identify and analyze the significance of potential hazards associated with the processing or handling of highly hazardous chemicals. Working with his safety manager, the staff member reviewed the shop’s equipment and the manufacturing processes and found that both needed improvement. He located a pressure action pump from GoatThroat Pumps that seemed to meet all of the goals – including efficiency.

“We understand the challenges that dispensing and mixing chemicals present to worker safety and environmental compliance, and we spend a lot of time in our pump lab working on how we can help our customers address them,” said Westcott. In the wire manufacturing facility, the pressure action pumps work by adding less than6 pounds per square inch of pressure to the vessel to push fluid out of the drum. A spring-activated control on the tap allows precise control of the amount of fluid being dispensed, a rate of 4 gallons per minute, depending on viscosity. There is no need for tipping the drums. According to the plant manager, “these pumps helped us improve our overall efficiency. By dispensing our chemicals from vertical drums, it has helped us clean up our dispensing area by eliminating drips and leaks. Another advantage is the ability to pump most of our drums almost completely empty. This alone saves us several thousands of dollars per month in disposal costs and chemical purchases. The company has been safely and more efficiently pumping chemicals without incident since 2004.