The tip-and-pour method, as well as poorly designed pumps, can expose workers to injury and companies to significant financial losses

Lawn care, landscape, golf course, and nursery handlers and applicators often transfer potentially hazardous chemicals and concentrates such as herbicides, insecticides, adjuvants, and fungicides, from large drums into smaller containers or mix tanks. This transfer process can have serious consequences if manual “tip-and-pour” techniques or poorly designed pumps are used.

In fact, each year 1,800-3,000 preventable occupational incidents involving pesticide exposure are reported. Keeping workers safe is not just a best management practice – it is the law. The federal Worker Protection Standard (WPS) was revised in 2015 and now provides a greater focus on reducing pesticide exposures. A closed system of transferring chemicals reduces unnecessary exposures by providing controlled delivery of chemical products without fear of worker exposure, over-pouring, spilling, or releasing vapors. Many of the revisions became effective this January.

“Beyond workers compensation issues related to exposure, there can be other huge potential liabilities: Environmental Protection Agency (federal) or state regulatory fines, as well as clean-up or remediation costs,” says Kerry Richards, Ph.D., President Elect of the American Association of Pesticide Safety Educators and former Director of Penn State’s Pesticide Safety Education Program. “This is particularly true if a pesticide gets into a water source, kills fish, or contaminates drinking water.”

According to Richards, the direct and indirect costs of a pesticide spill or injury can be substantial, not the least of which is the loss of wasted chemicals. “Pesticides, particularly newer concentrated formulations, are very expensive so spilling a few ounces could cost you several hundred dollars in lost product during a single transfer,” says Richards.

Although a number of pump types exist for chemical transfer (rotary, siphon, lever-action, piston and electric), most are not engineered as a sealed, contained system. In addition, these pumps can have seals that leak, are known to wear out quickly, and can be difficult to operate, making precise volume control and dispensing difficult.

In contrast, closed systems can dramatically improve the safety and efficiency of chemical transfer, as well as prevent the spillage or loss of valuable chemicals or concentrated formulations.

“The availability of new technology that creates a closed or sealed system is ideal for handling pesticides or other dangerous chemicals, and should become a best management practice,” suggests Richards. “With such devices, for example GoatThroat Pumps, pesticide handlers can maintain a controlled containment from one vessel to another and significantly reduce any potential for exposure or spill.”

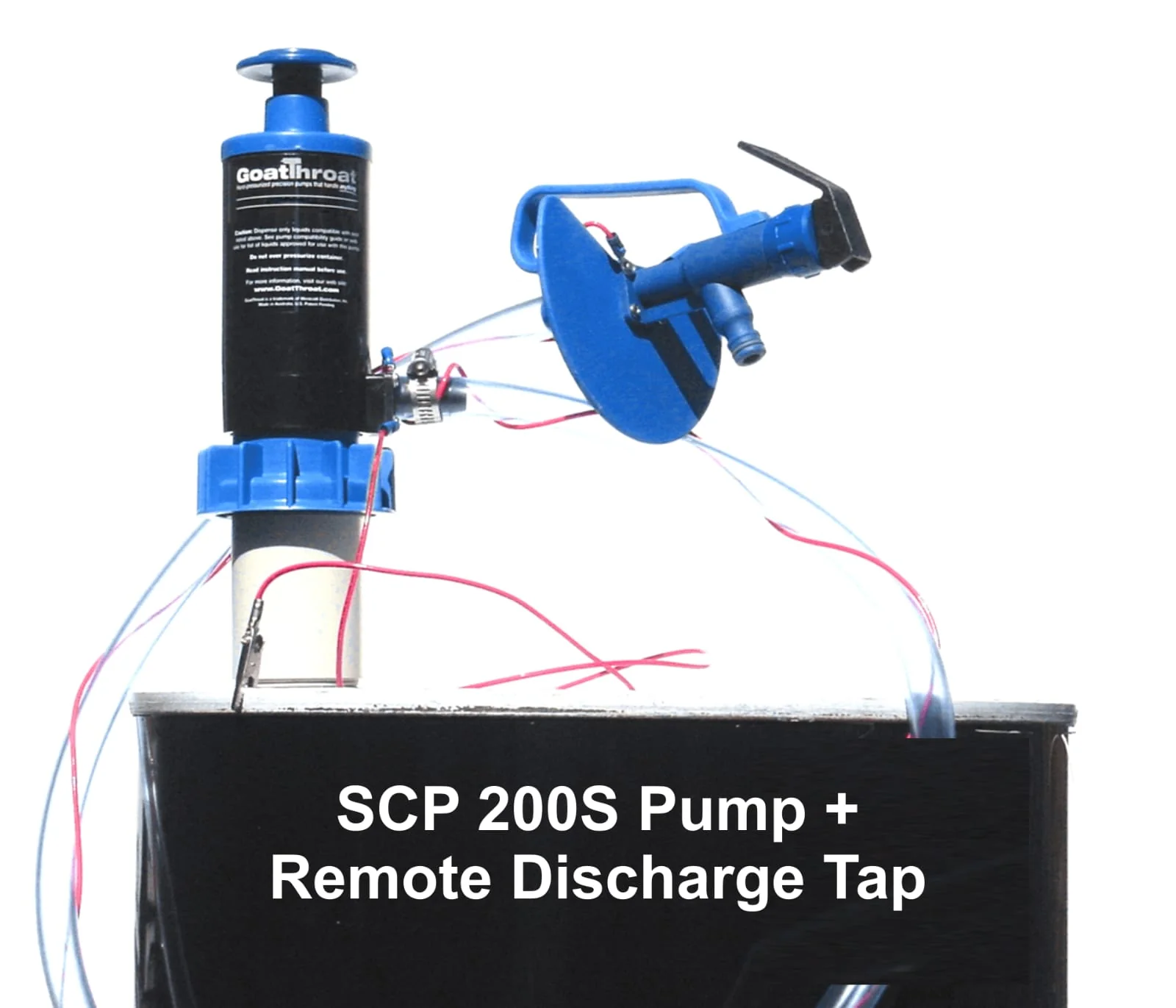

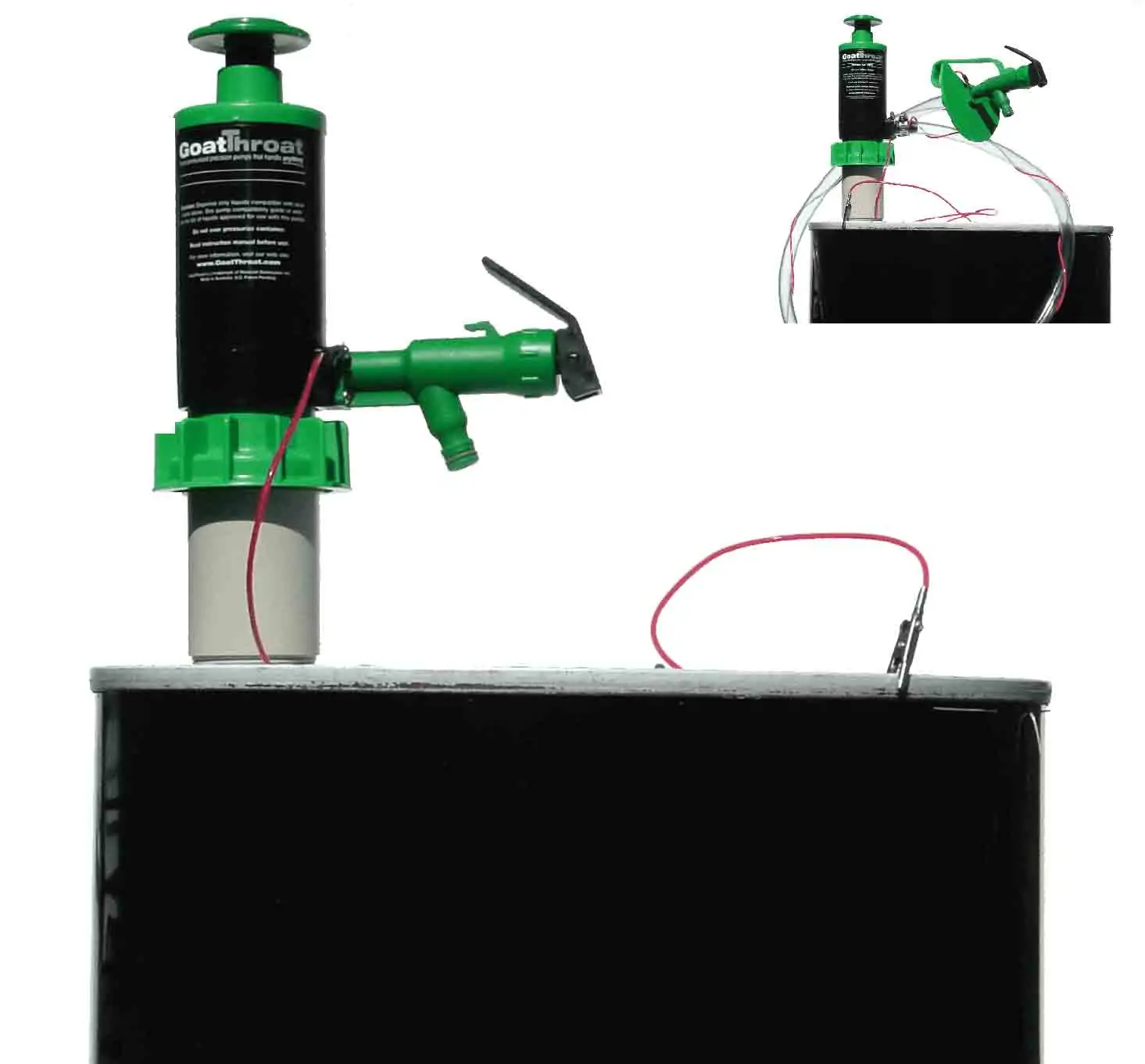

Small, versatile, hand-operated pressure pumps, such as those manufactured by GoatThroat Pumps, are engineered to work as a system which can be either closed or sealed. The pumps can be used for the safe transfer of over 1400 industrial chemicals, including the most aggressive pesticides. These pumps function essentially like a beer tap. The operator attaches the pump, presses the plunger several times to build up a low amount of internal pressure, and then dispenses the liquid. The device is configured to provide precise control over the fluid delivery, from slow (1ML/ 1 oz.) up to 4.5 gallons per minute, depending on viscosity, and are safe to use with virtually any container from 2-gallon jugs to 55-gallon drums.

Golf Resort Adopts “Best Practice” Pump Systems

Mike Cocino, assistant superintendent of Seaview Golf Resort in Galloway, NJ, sought a safer, more efficient way to transfer liquid fertilizers, wetting agents, biostimulants, and other plant growth regulators from 55 gallon drums to measuring containers. These would, in turn, be transferred to mix tanks ranging in size from 1 gallon hand pumps to 300 gallon sprayers.

Additionally, according to Cocino, sliding the heavy drums off of pallets with a dolly, and then tipping and pouring the drums was challenging, particularly in areas with limited storage.

“Drums can roll or fall, and you do not want to lose control of an entire drum,” says Cocino. “When tipping a drum, it’s difficult to pour out the right amount and easy to over-pour or splash some of the contents out.”

Cocino adds that getting to the needed drum typically required his staff had to move a few other drums out of the way, which was a laborious process.

To address these issues, Cocino purchased three GoatThroat Pumps and was happy with the results for a number of reasons.

“Safety is a huge priority for us, and with the sealed pumps we’re able to safely pump whatever product we need without moving or tipping any barrels,’” says Cocino. “The barrels stay safely in place, upright on their pallets, which definitely is a ‘back saver.’ Because of this, we’ve eliminated any issues of spillage or related cleanup.”

Cocino estimates that by avoiding the need to move the barrels, tip and pour product, and clean up any potential spills, his operation saves at least 50 hours of labor annually.